Crossing the Line: Sexual Harassment at School presents new evidence on sexual harassment, including cyber-harassment, in middle and high schools. It examines sexual harassment as reported in a nationwide survey of students in grades 7–12 conducted in May and June 2011. The survey confirms that sexual harassment remains an unfortunate part of school culture, affecting the educational experiences of millions of students, especially girls. Still, only a fraction of students who were sexually harassed during the 2010–11 school year reported the incident to a teacher or other adult at school. Many students told no one about their experience.

Unlike much of what I write about here, this is not simply an LGBTQ issue. The report finds that nearly half of middle and high school students are victims of sexual harassment. Since the LGBTQ community is upwards of ten percent of the population, this means that this is primarily a heterosexual problem. To be more fair in my wording, since it also involves many LGBTQ students, this is everyone's problem. From the Executive Summary

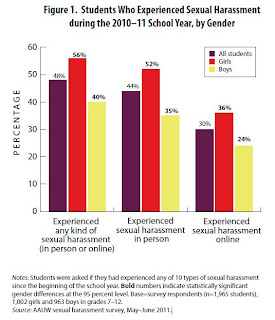

Sexual harassment is part of everyday life in middle and high schools. Nearly half (48 percent) of the students surveyed experienced some form of sexual harassment in the 2010–11 school year, and the majority of those students (87 percent) said it had a negative effect on them. Verbal harassment (unwelcome sexual comments, jokes, or gestures) made up the bulk of the incidents, but physical harassment was far too common. Sexual harassment by text, e-mail, Facebook, or other electronic means affected nearly one-third (30 percent) of students. Interestingly, many of the students who were sexually harassed through cyberspace were also sexually harassed in person.

The report finds that girls are more likely to be victims of sexual harassment than boys (56% of girls, 40% of boys). Being harassed for being gay or lesbian (whether or not the students really is) was equally divided (18% of all students). Again, since the LGBTQ community is upwards of 10% of the population, there are a lot of straight students who are harassed with allegations of being gay or lesbian. This is a problem for everyone.

An easy question to as is why teachers and principals are doing more to stop this. The report find that part of the answer is that sexual harassment is rarely reported to teachers and school administrators. Also from the Executive Summary

The prevalence of sexual harassment in grades 7–12 comes as a surprise to many, in part because it is rarely reported. Among students who were sexually harassed, about 9 percent reported the incident to a teacher, guidance counselor, or other adult at school (12 percent of girls and 5 percent of boys). Just one-quarter (27 percent) of students said they talked about it with parents or family members (including siblings), and only about one-quarter (23 percent) spoke with friends.2 Girls were more likely than boys to talk with parents and other family members (32 percent versus 20 percent) and more likely than boys to talk with friends (29 percent versus 15 percent).3 Still, one-half of students who were sexually harassed in the 2010–11 school year said they did nothing afterward in response to sexual harassment.

I am among the majority of teachers who do not see most of this happening. I admit this without knowing whether this is because I am subconsciously ignoring harassment (I hope not) or because it is well hidden from me (also bad, but more useful in understanding why I haven't seen this). Most teachers who I know will stop blatant harassment immediately. But that doesn't mean that it won't continue, perhaps via electronic media or in person outside of the classroom.

The numbers of harassed students during a single school year are perhaps more stunning in graphic format. From Chapter Two of the report

The chapter continues with a chart depicting the breakdown of different types of in-person sexual harassment. The most common was of the category "unwelcome sexual comments, jokes, or gestures to or about you." Second most frequent was "being called gay or lesbian in a negative way". These were followed by being forced to see something sexually undesired and then four categories of physical sexual harassment.

The reasons offered for sexual harassment are not surprising if one thinks about them. Most common was "it's just part of school life/it's no big deal". As explained in the conclusion of Chapter Two

A sizeable minority (18 percent of boys and 14 percent of girls) admitted that they sexually harassed another student during the 2010–11 school year. Most harassers felt that their actions were no big deal, and many were trying to be funny. Many stated that they were being stupid, which suggests that they view their actions as a mistake. Yet, students who admitted to being harassers are only a subsection of students who sexually harass others. The majority of sexual harassment remains unclaimed, suggesting either that the harassers are unaware of how others perceive their behavior or that they are unwilling to admit to it, even in an anonymous online survey.

Chapter Three looks at the effects of sexual harassment. It then discussed how the, sadly rare, interventions by other students took place.

When students witnessed sexual harassment and stepped in to help, they were most likely to tell the harasser to stop or to see if the sexually harassed person was okay. Many students who witnessed sexual harassment did nothing simply because they did not know how to respond, did not think it would make a difference, or feared that they would become targets themselves.

As education communities, we are failing to help. From Chapter Four

Only 12 percent of students surveyed felt that their school did a good job addressing sexual harassment, and more than two-thirds of those students had not been sexually harassed during the 2010–11 school year. Of the remaining students, nearly all thought that their schools could and should do something about sexual harassment.

Strategies for addressing sexual harassment at school are most effective when they come from the top. Studies show that if administrators such as principals tolerate sexual harassment or do nothing to address it, teachers and students have less incentive and less support to do anything about it (Lichty & Campbell, 2011; Meyer, 2008).

Chapter Four continues to detail what different members of the education community can and should do. The various lists of recommendations are fairly long. As an example, here is what is recommended for teachers who observe sexual harassment

- Name the behavior, and state that it must stop immediately.

- Suggest an appropriate alternative to an offensive word or phrase and advise students to use it going forward.

- Use the incident as a reason for talking to students about sexual harassment, what it is, and why it’s not okay.

- Follow the school policy for handling sexual harassers.

- Send the person to the principal or guidance counselor, and notify the families of the students involved as necessary.

This list of excuses that I have just given are not intended as a call of "don't blame me." Rather, these are real circumstances of which all parties should be aware prior to casting blame for a broken system. Teachers are part of the blame but cannot own all of it.

The full report is clearly presented and well worth reading.

No comments:

Post a Comment

No longer open for freely commenting.